This is the fifth installment of an article on the Kingdom of God.

Part 1 began with Jesus’s proclamation at the start of his ministry about the kingdom of God. Part 2 looked at Jesus’s sermon at Nazareth, in which he explained the nature of the kingdom he was inaugurating.

Part 3 shifted to the biblical backstory of the kingdom, beginning with the royal calling of humanity created to image God, including how we squandered our calling through sin and violence, culminating in the tower of Babel. Part 4 traced the story of Israel from Abraham to the Babylonian exile, with a focus on the theme of “rule” (power and agency).

Against the backdrop of the kingdom of God in the Old Testament, the current installment picks up the story with the ministry and mission of Jesus, leading to his confrontation with the powers in Jerusalem at Passover.

The Rise of Messianic Expectation

Israelite prophets during and after the Babylonian exile began to articulate an expectation of renewal for God’s people, which intensified as the first century approached. God was going to bring about a new age of righteousness and justice for Israel and for the entire world.

As the Isaiah passage Jesus quoted at Nazareth made clear (see part 2 of this multi-part blog post), the prophetic vision of social and personal healing that arose in the exile remained unfulfilled even after Israel was back in the land. Isaiah 58 and 61 both addressed the moral state of the people, which had not changed; they continued to be embroiled in sin and disobedience to God. So beyond the bare fact of return to the land, the rest of the prophets’ vision of restoration had not yet come to pass.

It was this lack of fulfillment that generated messianic hope in the centuries leading up to the New Testament. The term Messiah (lit. anointed one) is derived from the fact that the kings of Israel were anointed for their leadership role (1 Samuel 9:26–10:1; 1 Samuel 16:12–13). The hope for a Messiah (a royal leader, in the lineage of David) arose out of the obvious failure of the Israelite monarchy in combination with God’s promise that the people would once again have righteous leaders.

The dominant messianic expectation was of a new Davidic king who would unify the nation and cast off Roman oppression, yet ideas about the coming Messiah were actually quite varied: would there be one or two leaders (one royal, the other priestly); would the agent of God’s coming rule be human, angelic, or divine?

Despite this variety there was a consistent expectation that one day God would establish his righteous rule both in Israel and throughout the world. The coming of this kingdom would eradicate evil and restore justice for God’s people and among all the nations. Indeed, the entire cosmos would be renewed, such that this coming age could rightly be called “a new heaven and a new earth” (Isaiah 65:17–25).

Jesus’s Confrontation with the Powers of Evil

It was this expectation for a radical reorientation of the world that set the stage for the ministry of Jesus, including his proclamation that the kingdom of God was at hand, his teaching about the kingdom (often in parables), and his embodying the kingdom in his healings, his exorcisms, and his forgiving of sins. Jesus both announced and demonstrated that the powers of evil were being overthrown, that God’s rule was coming.

But the powers of evil are never easily overthrown. Jesus encountered opposition throughout his ministry, which led to his crucifixion by a coalition of Roman and Jewish leaders, who considered him a threat to the status quo. Jesus was not, however, a passive victim of his opponents. His entire life and ministry were oriented towards this deathly confrontation.

The Messiah’s Destiny of Suffering

After three years of his public ministry, Jesus asked his disciples who they thought he was. When Peter confessed that he was “the Messiah of God” (Luke 9:20), Jesus explained that his destiny (in contrast to most messianic expectation of the time) was not immediate victory over the powers of evil. His destiny was suffering and rejection at the hands of “the elders, chief priests, and scribes,” resulting in his death—followed by resurrection (Luke 9:22; this episode is recounted in Matthew 16:21–23; Mark 8:31–33; Luke 9:21–23).

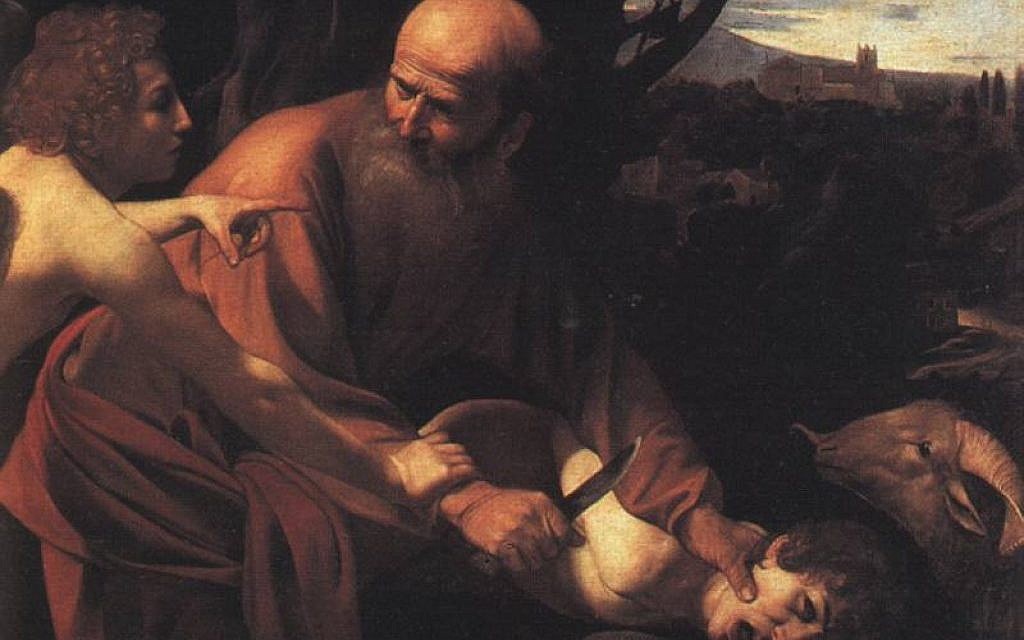

Jesus understood that the Messiah’s destiny of the ultimate triumph over evil was grounded in his suffering on behalf of his people—a theme found in what are known as the servant songs of Isaiah. These prophetic poems, in that section of the book written during the Babylonian exile (Isaiah 40–55), affirm that Israel is God’s servant (Isaiah 41:8; 49:3), whose mission is to bring light to the nations and to establish justice throughout the earth (Isaiah 42:1, 4, 6). This understanding of Israel as God’s servant draws on God’s promise that through Abraham and his descendants blessing would come to all the families of the earth (Genesis 12:1–3).

Yet in Isaiah’s servant songs, Israel is said to be a blind and deaf servant who does not understand or obey God’s purposes (Isaiah 42:19–20), This leads to a distinction between the servant and Israel in some texts; there the mission of the servant of YHWH is to bring light not only to the nations, but also to Israel (Isaiah 49:5–6).

While Isaiah 50 mentions briefly that the servant will suffer before his vindication by God (Isaiah 50:5–8), this theme is explored in depth in Isaiah 52:13–53:12, the so-called Suffering Servant song. The New Testament understands this vivid portrayal of the servant’s suffering to be fulfilled in Jesus, understood as the representative of Israel (Matthew 8:14-17; Luke 22:35–38; John 12:37–41; Acts 8:26–35; Romans 10:11–21; 1 Peter 2:19–25).

Jesus Sets Out for Jerusalem

Soon after Jesus predicted his suffering and death, he set out to meet his destiny. Perhaps alluding to Isaiah’s servant who “set [his] face like flint” to endure opposition (Isaiah 50:7), Jesus “set his face to go to Jerusalem” (Luke 9:51).

As he journeyed toward Jerusalem, stopping in other places on the way, he twice more reminded his disciples of his coming death (first in Matthew 17:22–23; Mark 9:30–32; Luke 9:43–45; then in Matthew 20:17–19; Mark 10:32–34; Luke 18:31–34); this was clearly on his mind.

In each case, his disciples found this difficult to comprehend; wouldn’t this mean the defeat of the Messiah? Even after Jesus reached Jerusalem, he again reminded them of his destiny (Matthew 26:1–2).

Jesus and the New Exodus

Not only did Jesus intentionally embrace his destiny, he chose the timing of it to coincide with the festival of Passover, when pilgrims were flocking to Jerusalem to celebrate the exodus from Egyptian bondage. But no-one in Jerusalem would have focused simply on that event in the past. Isaiah 40–55 had already viewed Babylon as a new Egypt and the return from Babylonian exile as a new exodus. The city would have been rife with expectation: would God act again to free his people from the latest incarnation of Egypt and Babylon?

Some centuries before Jesus, the Persians had conquered the Babylon empire and allowed exiled Jews (inhabitants of Judah) to return to their homeland; so technically the exile was over. But after Babylon’s defeat, Judah (now known as Yehud) became a province of Persia, After that came the Greek empire, and finally the Romans—all of whom continued to subject the land and people of Israel to imperial domination. It would have been impossible for Jews in Jesus’s day to separate the message of the exodus of old from the need to be liberated from Roman oppression. A new exodus was called for.

Continuing Bondage and Exile

The idea that Israel was still in bondage—even after return to the land—is expressed in the anguished prayer of Ezra, the Jewish scribe and priest, during the early postexilic period:

“Here we are, slaves to this day, slaves in the land that you gave to our ancestors to enjoy its fruit and its good gifts. Its rich yield goes to the kings whom you have set over us because of our sins; they have power also over our bodies and over our livestock at their pleasure, and we are in great distress.” (Nehemiah 9:36–37; see also Ezra 9:8–9)

The Babylonian exile was over, but the bondage to foreign empires continued unabated.

The problem, however, was not simply the external oppression of empires. The internal problem of sin had to be dealt with. The prophets had declared that the Babylonian conquest and the ensuing exile was a consequence of Israel’s disobedience to God (Jeremiah 32:28–35; Isaiah 42:24–25; 43:27–28). This was a fundamental difference between Egyptian bondage (which was not attributed to Israel’s sin) and the Babylonian exile (which was).

Ezra himself combined recognition of continuing national bondage with the people’s ongoing sinfulness. “From the days of our ancestors to this day we have been deep in guilt, and for our iniquities we, our kings, and our priests have been handed over to the kings of the lands, to the sword, to captivity, to plundering, and to utter shame, as is now the case” (Ezra 9:7).

Now, even back in the land, the moral state of the people remained unchanged; their sin still had to be dealt with.

As we shall see in the next installment, the problem of Israel’s bondage was greater than either the external oppression by empires or the internal sinfulness of the people.