In my last blog post I reported on the theology conference on the theme of “Biblical Interpretation for Caribbean Renewal” that I helped organize at the Jamaica Theological Seminary (JTS) in Kingston (September 8-9, 2017).

A Visit to Culture Yard in Trench Town

The conference began Friday night and ended late Saturday afternoon.

Then on Sunday four of us from the conference went on an informal tour of two famous Rastafari sites. The four were Garnett Roper (the president of JTS), Winston Thompson (vice-president of JTS), Christopher Duncanson-Hales (a presenter from Canada, who had made Rastafari his primary research over the years), and myself.

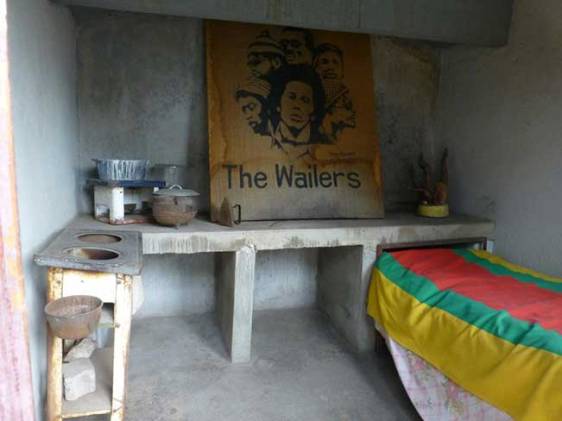

First, we visited Culture Yard, the heritage site that was the small complex of buildings Bob Marley used to live in when he was just starting out in Kingston. This was the famous “government yard in Trench Town” mentioned in the song “No Woman No Cry.”

One of the rooms around this central open “yard” (courtyard) was the kitchen with Marley’s “single bed” (mentioned in the song “Is This Love“).

Even Marley’s first (well-used) guitar was preserved for visitors to see.

Our tour guide was a Rasta named Stone Man, because of his stone carvings with mystical glyphs and spiritual meanings.

A Journey to the Historic Rastafarian Camp at Pinnacle

After Culture Yard, we journeyed into the Jamaican countryside, to the parish of St. Catherine, to visit Pinnacle, the site of one of the earliest Rastafarian camps in Jamaica.

So named because it is situated on a hilltop, Pinnacle was founded in 1940 by one of the first Rastafarian preachers, Leonard Howell (sometimes called the First Rasta, though he had no dreadlocks).

Pinnacle soon became a model for other Rasta settlements throughout Jamaica, focused on self-sustaining agriculture (which also included ganja cultivation). Partially because of the ganja, but also because of suspicions that Howell was sowing sedition (this was before the wider culture and the police came to understand Rastafari), Pinnacle was raided a number of times by the police in the nineteen forties and fifties. After the final raid, the Rastafarians who lived there dispersed throughout the island.

It has only recently been restored as a Rastafarian Heritage Site and Cultural Centre by the government of Jamaica.

While at Pinnacle, we met the Rasta who takes care of the grounds, including the ruins of the house where Leonard Howell used to live.

He explained to us the history of Pinnacle, including its current use from time to time for Rastafarian meetings with Nyabingi drumming and chanting.

Although Nyabingi is the name of one of the Mansions (groups or denominations) of Rastafari (“In my Father’s house are many mansions”; John 14:2), Nyabingi is also a form of rhythmic drumming and chanting used in Rastafari ceremonies. “Rastaman Chant” by Bob Marley and the Wailers is based on the Nyabingi classic, “Babylon Throne Gone Down.”

In a follow-up post, I describe a research project (and book) on Rastafari that I may be involved in, spearheaded by Christopher Duncanson-Hales, the Canadian presenter at the JTS theology conference who has made Rastafari his major research over the years.