Here is a blog interview that New Testament Professor Nijay Gupta did with me last year for part of a series he was posting on Old Testament scholars.

NOVEMBER 9, 2020 BY NIJAY GUPTA

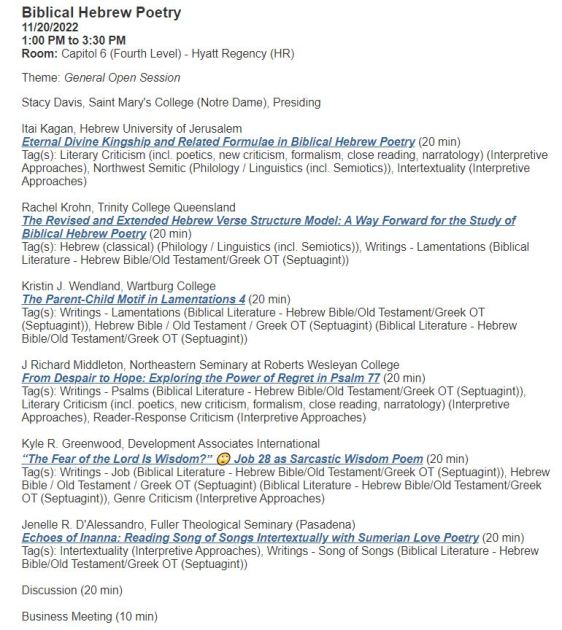

Richard Middleton, Professor of Biblical Worldview and Exegesis, Northeastern Seminary at Roberts Wesleyan College

Why do you love teaching and researching about the OT/HB?

I find the Old Testament to be rich, complex, and textured—in its literature, its theology, and its earthy spirituality. The literature is so varied (from creation texts to prayers of lament, from wisdom treatises to narratives about the ancestors of Israel and the rise and fall of the monarchy), it’s impossible to get bored with it. One of the great challenges for those who teach the Old Testament is that it is impossible to “master” it. You develop various areas of expertise, but there is always so much more that you have to learn.

The earthiness of the Old Testament is also a great antidote to some of the otherworldly spirituality that has become embedded in the history of the church. Since the Old Testament was the Scripture of Jesus, Paul, and the early church, it was the story and symbolic world in terms of which they mapped their lives and God’s plan of redemption for the ages. This means that it is essential for us to understand the worldview of the Old Testament, since it shapes the New Testament in a fundamental way. So my study of the Old Testament has led me to become a better reader of the New Testament.

What is one “big idea” in your scholarship?

I think I have two big ideas, or at least two emphases, that I hope I have been able to communicate in my teaching and writing. When I started teaching at Northeastern Seminary, the Dean suggested I take the title Professor of Biblical Worldview and Exegesis, since these were my twin emphases.

The first emphasis that I want to communicate is the big picture, the story of the Bible from creation to eschaton, which is the story that ought to make sense of our lives (the trouble is that many in the church have “lost the plot”). So the big picture can help reorient the church to its vocation (the missio Dei), how it is called to contribute to the unfolding of God’s purposes for the world God loves. For me, this has meant a focus (initially, at least) on creation texts, whether in Genesis, the Psalms, Job, or the prophetic literature. Creation is the founding moment of the biblical story and studying these texts helps us see God’s original intentions for humanity and the world, which have something to say about the telos or goal of salvation.

The other big idea that I want to communicate (and model) is that careful reading of the biblical text yields wonderful theological and ethical results. I’ve tried to show precisely that in exegesis courses that I teach on Genesis, Samuel, Job, and the Psalms. This means reading with an inquiring mind, wondering why the text says what it does, and why it says it in the way that it does. It means bringing the entirety of who we are to the study of the Bible, including our hopes, our doubts, our assumptions, our questions, and being willing to challenge the text—so long as we are willing to be challenged in response. The Bible is not a safe book; it can radically change us.

Who is one of your academic heroes and why do you admire them?

My first academic hero is Walter Brueggemann. Although I haven’t always agreed with Brueggemann (I’ve written an article critical of his creation theology, and he graciously accepted my critiques), his attempt to bridge the gap from the ancient biblical text to the contemporary world has inspired me to try and do the same. He particularly opened up to me the riches of the prophetic literature and the Psalms.

What books were formative for you when you were a student? Why were they so important and shaping?

When I was an undergraduate theological student, I was profoundly affected by George Eldon Ladd, The Pattern of New Testament Truth. In that book Ladd tried to sketch the Synoptic pattern, the Johannine pattern, the Pauline pattern, and also to address the Old Testament pattern that undergirded the New Testament. Whether or not I would fully agree with his analysis of the New Testament today, his attempt to show both diversity and coherence in the New Testament text was very helpful. But most helpful of all was Ladd’s chapter called “The Background of the Pattern: Greek or Hebrew?” where he did detailed textual study of Plato, Philo, and the Old Testament to address whether the Old Testament pattern was human ascent from the world to God or God’s descent from heaven to earthly existence.

When I was a graduate theological student, it was Brueggemann’s books that deeply impacted me—first The Message of the Psalms: A Theological Commentary, then The Prophetic Imagination. I still assign them in courses.

Read Middleton’s Work

The Liberating Image: The Imago Dei in Genesis 1

A New Heaven and a New Earth: Reclaiming Biblical Eschatology

If you ran into me at SBL, and you didn’t want to talk about OT/HB studies, what would you want to talk about?

I would probably talk about music—especially reggae (both from my home country and “world reggae”) and the music of Bruce Cockburn and Leonard Cohen.

What is a research/writing project you are working on right now that you are excited about?

I am now finishing the final chapter of a book on the Aqedah (Genesis 22) for Baker Academic. It’s called: Abraham’s Silence: The Binding of Isaac, the Suffering of Job, and How to Talk Back to God. It’s a theology of prayer for a time of suffering, developed through interaction with biblical texts (the only way I know how to do theology).

Update: Abraham’s Silence is now complete (published November 2021). For information, see the Baker website.

For those interested, there is a recent review of Abraham’s Silence, called “Revisiting the Sacrifice of Isaac.”